T0. sum and prod

Warning, all conclusions appear in the text may be wrong.

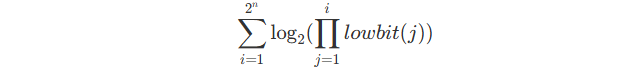

First copy the formula :

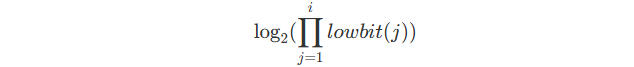

Start from this part :

Studying a product is mych harder than a sum, so we need to translate this part into a sum.

Everyone knows that \log_a(bc)=\log_a b + \log_a c

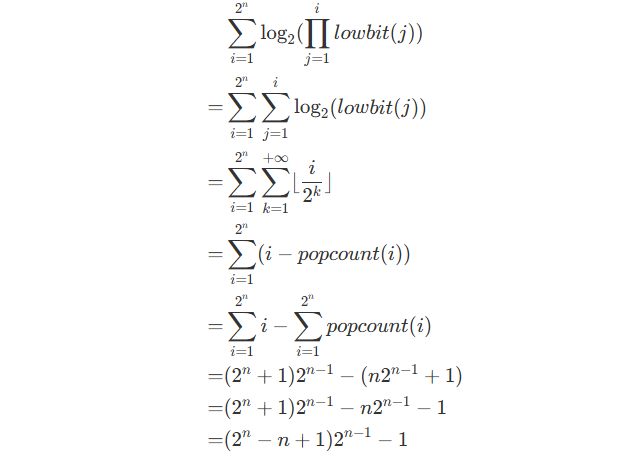

So this part will be :

Now stydy the pattern of lowbit(x) .

| x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2^0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2^1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2^2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2^3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| lowbit(x) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| log2(lowbit(x)) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

We can find that log2(lowbit(x)) has a special pattern :

There are many similar parts, such as (0, 1, 0, 2) and (0, 1, 0, 3), etc.

If we study further, we can find for all odds, the formula is 0, for all evens, the formula is greater than 1, etc.

But, why?

Think about the definition of lowbit(x) , it means that the end of x has a series of 0, with a length of \log_2(lowbit(x)) .

Think more about what zeros at the end in the binary expression means.

If we divide x by 2, it equals to right-shift this number in the binary expression.

During this process, the last digit will be lost.

However, if the end of this number is 0, even if we lose this number, if we left-shift this number, the end is still 0, so the number do not change.

But if the end of this digit is 1, a right-shift operation will make it lost, cannot be restored by left-shift operation.

So, if a number ends with 0 in the binary expression, it can be divided by 2.

Generally, a number can by divided by 2^k , if and only if doing k right-shift operations and k left-shift operations do not change the number, i.e. the number ends with k zeros.

Now think back on the definition of lowbit(x) .

In the binary expression, the digit on 2^{\log_2(lowbit(x))} is exactly 1, and after this digit is a series of 0.

Connect these statements together, we can get under conclusion :

$lowbit(x)$ is the maximum k that satisfies : Doing k right-shift opeartions and k left-shift opeartions on x do not change it.

i.e. x \mid lowbit(x) and x \nmid (2lowbit(x)) .

So, in that table, if 2^k \mid x , we can get lowbit(x) \ge k .

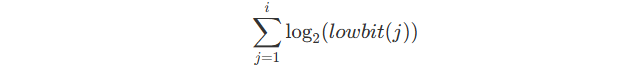

Now think about the sum in the 2nd layer.

Base on conclusions above, we can get an idea on how to calculate this sum.

- There are \lfloor \frac{i}{2} \rfloor numbers that can be divided by 2, i.e. their lowbit(x) \ge 1 .

- There are \lfloor \frac{i}{4} \rfloor numbers that can be divided by 4, i.e. their lowbit(x) \ge 2 .

- There are \lfloor \frac{i}{8} \rfloor numbers that can be divided by 8, i.e. their lowbit(x) \ge 3 .

- and so on…

Notice that every part includes after parts, so when we calculate their contribution to the sum, the scale is 1 instead of other strange numbers.

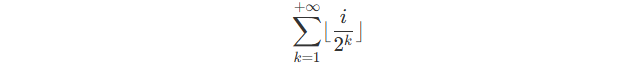

This part will be :

According th the conclusions above, \lfloor \frac{i}{2^k} \rfloor is the result of doing k right-shift operations on i.

So try to study the binary expression of i.

Suppose $i=(ak a{k-1} a_{k-2} … a_2 a_1 a_0)_2$ .

Now we only focus on a non-zero digit a_p .

Before any operations, its value is a_p2^{p} .

After 1 right-shift operation, its value is a_p2^{p-1} .

After 2 right-shift operations, its value is a_p2^{p-2} .

…

After p-1 right-shift operations, its value is a_p2^{1} .

After p right-shift operations, its value is a_p2^{0} .

After p+1 right-shift operations, its value is 0 .

…

After +\infty operations, its value is 0 .

So, for a digit a_p in i, its contribution to the answer is $ap\sum{k=0}^p 2^k, i.e.ap(2^{p+1}-1).

So, the contribution of i to the answer is\sum{p=0}^k ap(2^{k+1}-1).

The sum is also equal to\sum{p=0}^k ap2^{k+1} – \sum{p=0}^k a_p = i-popcount(i)$ .

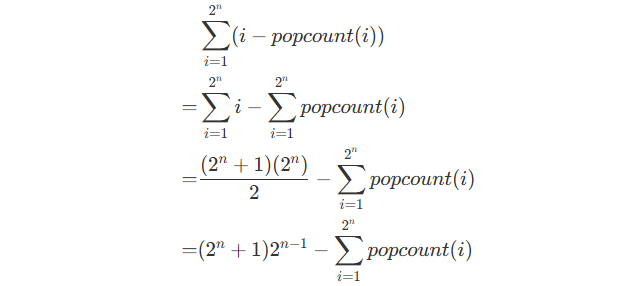

Therefore, the final sum is :

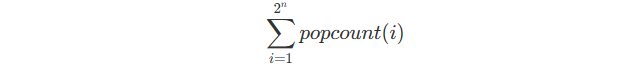

Now, we have only one term to solve :

We still think about the contribution of every digits.

Write down the binary expression of every number from 1 to 2^n (take n=3 for example)

| Decimal | Binary |

|---|---|

| 1 | (0001)2 |

| 2 | (0010)2 |

| 3 | (0011)2 |

| 4 | (0100)2 |

| 5 | (0101)2 |

| 6 | (0110)2 |

| 7 | (0111)2 |

| 8 | (1000)2 |

We can find that except the 2^n (here it is 2^3) digit, all digits have exactly 2^(n-1) ones.

But why?

Since the condition of i=2^n is special, we first study the region [1, 2^n-1] .

In this region, the binary expressions of numbers can enumerate all possible combinations of 0 and 1 except 0=(000…000)_2 .

For the digit 2^p (p \ne n) :

- When a_p=0 , since the digits are independent, the remain digits have 2^{n-1} possibilities. However, because one of these possibilities 0=(000…000)_2 is not in the region, so there are actually 2^{n-1}-1 possibilities.

- When a_p=1 , the remain digits have 2^{n-1} possibilities. We can ensure that all possiblities are valid.

So, in the region [1, 2^n-1] , the contribution of every digit to that term is 2^{n-1} .

Since there are at most n non-zero digits, the contribution of this region to that term is n2^{n-1} .

And, do not forget i=2^n .

In this case, only the 2^n digit is 1, so its contribution to that term is 1.

So, that term also equals to :

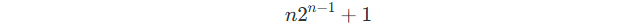

So the final answer is :

The term of 2^n and 2^{n-1} can be computed with a complexity of O(\log_2 n) .

Since n \le 2^{62} , it can pass this problem.

Code :

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

const long long MOD=1000000007;

long long qkpow(long long a, long long e) {

if (e==0) return 1;

if (e==1) return a%MOD;

long long HF = qkpow(a%MOD, e/2);

if (e&1) return (((HF*HF)%MOD)*(a%MOD))%MOD;

return (HF*HF)%MOD;

}

int main() {

long long N;cin >> N;

long long res=((((qkpow(2, N)-N%MOD+1+MOD)%MOD) * (qkpow(2, N-1)%MOD))%MOD-1+MOD)%MOD;

cout << res;

return 0;

}

(Thanks : ymh : submitted the code.)